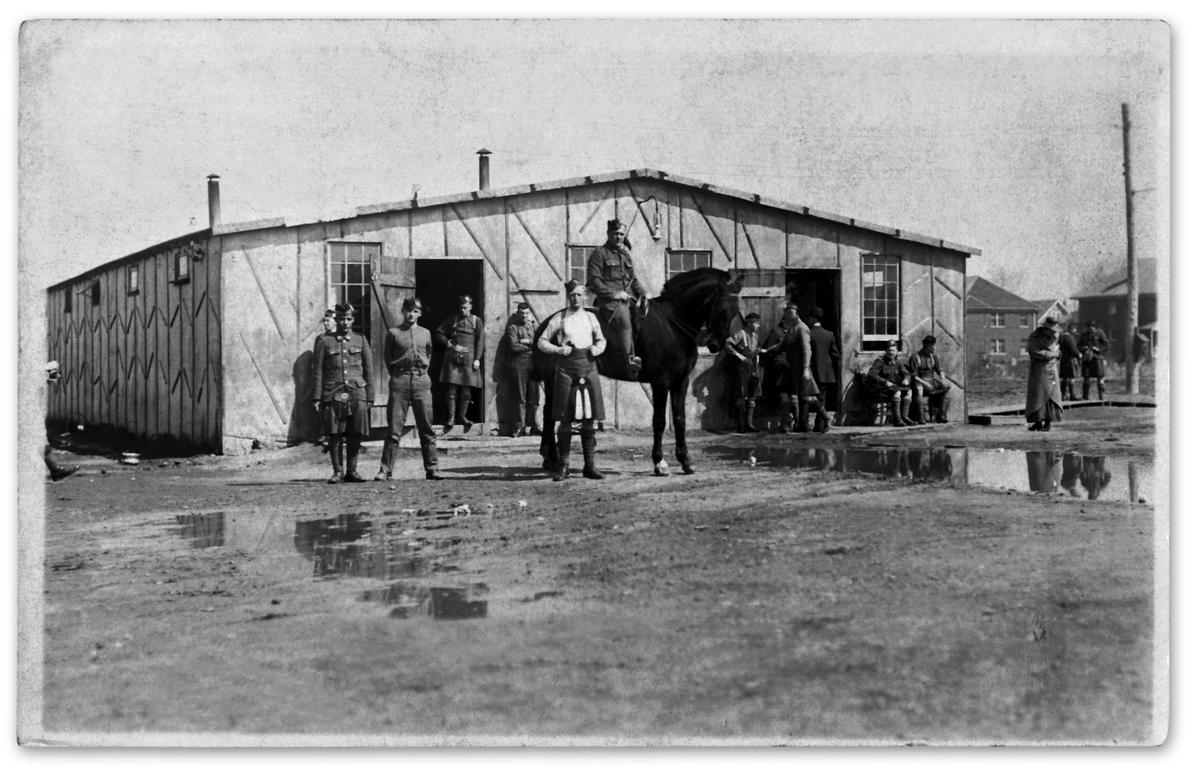

241st Battalion, Canadian Scottish Borderers, C.E.F.

241st Battalion at barracks in Windsor, 1916.

The 241st Battalion, Canadian Scottish Borderers, Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) was the third battalion raised in the Windsor area during the First World War. After months of deliberation, it was raised in May 1916 under Captain Walter Leishman McGregor Sr. The battalion was to be a highland regiment with traditional kilts and a pipe band. As a veteran of the 21st Essex Fusiliers since 1898 and the son-in-law of Lieutenant-Colonel Ernest Wigle of the 18th Battalion, McGregor was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and chosen to lead the new unit.

The proposal for a new highland unit was motivated by the desire to increase enlistment after the initial group of willing Canadian men had already crossed the ocean to fight in the European conflict. With the impracticality of kilts for trench warfare and the cost involved in creating the new unit, Minister of Militia, Sir Sam Hughes allowed for the creation of the battalion but would not permit the government to subsidize the cost of the kilts. However, local leaders felt that the kilt was essential to recruitment. Furthermore, they argued that kilts would help to reduce desertions and allow the unit to reach full strength more quickly. McGregor was heavily involved in promoting the unit and insisted that the men did not have to be Scottish to enlist. He also advocated the acquisition of the “Hodden Grey” tartan kilts for the regiment.

However, there was no appropriate place to train the soldiers at the time. The city allocated $2,000 for a camp in Windsor, alongside $10,000 and $3,000 given by the town of Walkerville and the city of Windsor respectively to purchase the kilts. By the end of July 1916, the camp was established on Dougall Avenue and Tecumseh Road.

The camp was built as the Battle of the Somme raged overseas, which disillusioned many new recruits due to its carnage and high casualty rates. Efforts to increase enlistment numbers were vigorous, including hosting public picnics and planned appearances by the unit’s men such as Pipe Major Jock Copland. McGregor appealed to local women to convince the men in their lives to join the unit, while Major Edward Kenning stated that many men who were loyal to him agreed to go overseas when he went. The regiment sent letters to young businessmen asking if they would join the regiment with little success. Recruitment efforts were disappointing; it was published in the newspaper that the regiment would “appreciate a little more enthusiasm” about the new unit from local men. By that point, only 114 men from Essex County had enlisted. The men filling the regimental ranks came in large numbers from the United States, Russia, and parts of western Ontario.

However, winter quickly approached, and the local camp needed to prepare for the cold weather. Many men who enlisted were employed to make renovations on the building while staying under the $4,500 repair budget. The goal had been to reach full regimental strength by the New Year, but by October 1916 the battalion had only grown to five hundred men. Local pastors and members of the regiment delivered speeches and sermons on “Military Sundays” imploring men to enlist. Lieutenant-Colonel Wigle spoke at rallies in hopes that he might inspire men to sign up. On 12 November 1916, “Patriotic Sunday” was also held in Kingsville and Leamington wherein members of the battalion spoke to congregations of all the area’s churches. However, these efforts cumulated in little impact on the unit’s numbers. Other regiments were not permitted to recruit on Ouellette Avenue so that the 241st may have sole access to men coming across the river from Detroit.

The battalion was unable to go overseas as a unit due to their failure to reach the threshold of seven hundred men. After the Battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917, deserters were rounded up and the unit prepared to go overseas. Soldiers of the 241 st Battalion were not permitted to march in the Michigan Marine parade that was sending troops off due to their non-unit status, but some soldiers attended while on leave anyway.

552 men from the unit boarded the S.S. Olympic in Halifax on 1 May 1917. They were given socks, cigars, and baked goods as parting gifts. They reached England on 8 May. All but two of the twenty-three officers to go overseas were Canadian, as was typical of battalions from Essex and Kent counties. Approximately thirty-six percent of the battalion were born in Canada. Twenty-seven percent of the battalion was American, most being from Michigan.

Upon landing in Europe, the group was broken up to reinforce other units. Private Clarence Ormand Freeman was the only fatality of the 241st Battalion who served with the 18th Battalion. Seventy-five fatal casualties occurred to former members of the 241st when they were sent to the frontline units. The unit experienced many of these casualties at Passchendaele in November 1917.

241st Battalion member Lieutenant A.T. “Tower” Ferguson earned the Military Cross for his actions at Amiens. Sergeant James A. Roberts was awarded the Military Medal at Passchendaele.

The men returned to Canada with the battalions they served with during the war, meaning that only a few men returned at a time. Lieutenant-Colonel McGregor welcomed them back when they were repatriated and helped them to return to civilian life.

The battalion received the The Great War 1917 battle honour, which was eventually perpetuated by the Essex Fusiliers.

Story by Nicole Pillon, Canada Summer Jobs 2022 participant

with The Essex and Kent Scottish Regiment Association

Sources

Duty Nobly Done: The Official History of the Essex and Kent Scottish Regiment by Sandy Antal and Kevin R. Shackleton, 2006: Chapters 8, 9